by Gifford and Eileen Eardley

One is apt to think that the present busy shopping centre, with its frontage sited along portion of the length of Railway Parade, would date back to the rural days of the district, but this is not so. The earliest business centre of Kogarah faced Rocky Point Road and for the most part was located between St Paul’s Church of England and St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church, with the old established Gardiner’s Arms Hotel at the junction with the then Kogarah Road, now portion of the Prince’s Highway.

The coming of the first section of the Illawarra Railway, which opened between Sydney and Hurstville on October 15th, 1884, gave the present shopping centre its first impetus. These premises, few in number at that time, were clustered together in the immediate vicinity of the then new a railway station. Prior to this development the location was more or less a scrub-covered sandstone hilltop, noted for its caves and rocky escarpment, one particular cave, so it has been related, was used as a bushranger’s cache in the days of yore. The land was cleared and rocks razed to form streets, shopping and household allotments, but the base rock formation of the area can still be seen in the cutting at the northern end of Kogarah Railway Station in the vicinity of the overhead road bridge.

Kogarah Railway Station, in its original form, consisted of two opposed platforms now denoted as numbers 3 and 4, that on the “Up” or western side may be regarded as being the most important as the brick buildings housed the stationmaster’s office and the goods office. Each platform had its separate ticket office and waiting room, etc. There was a carriage drive also on the western side for the convenience of those fortunates who were driven in horse drawn vehicles to the station. The southern end of the “Down” platform was provided with a short dock platform against which the steam trams to and from Sans Souci were accommodated. A foot crossing over the railway and tramway tracks was located at the southern end of the platforms, and appears to have been replaced by an overhead bridge, built up from discarded rails, about the beginning of the present century.

Outside the “Down” platform an excavation had been made in the adjacent hillside in order to give hansom cab and horse omnibus access to the station exits. These transport facilities were in great demand on the occasions when meetings were held at the Moorefield Racecourse. This station roadway also came into use when funeral corteges arrived to meet the Funeral Trains which ran, with the utmost decorum, to the Woronora Cemetery near Sutherland. We recall the four-wheeled glass-sided hearse, drawn in solemn state by two well-groomed black horses, and the accompanying mourning coaches that were to be seen on these sad occasions, together with a retinue of sulkies and other vehicles conveying friends to the station, and its designedly slow moving steam train.

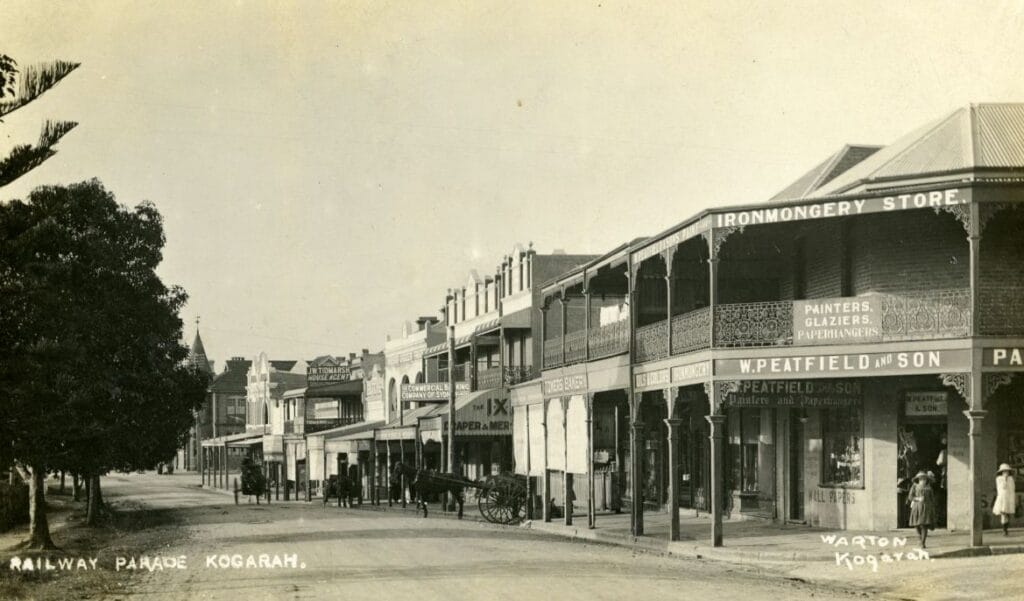

The main thoroughfare, known as Railway Parade, commenced at Harrow Road and ran west to meet the Illawarra Railway which it then skirted on the eastern side, with one minor divergence at the crest of Kogarah Hill to avoid the station-master’s residence, until the original alignment of Forest Road was met at the overbridge immediately north of Hurstville Railway Station. However, for the purpose of this essay we are only concerned with that section of Railway Parade which extends from the intersection of Montgomery Street at Kogarah to the intersection of Gray Street. The eastern side of this section now forms a large portion of the main shopping centre. For historical reasons we have taken the period of the early nineteen-noughts, an era with which we are personally acquainted.

The Railway Parade of those now far off days was surfaced with small blocks of packed random-shaped sandstone, material which quickly disintegrated into dust under the impact of the horses’ iron-shod hoofs and the passage of many iron-bound cart-wheels in windy weather, particularly when the westerly winds of winter were blowing, the road dust rose in smothering clouds, intermixed with whirling paper and refuse swept daily from the footpaths. Shop-keepers brought out lengths of garden hose on these occasions and sprayed water onto their display windows, their portion of the-footpath, and the adjacent roadway to the full extent of the jet in order to give some measure of relief. In wet weather the roadway became a slithering sea of mud, intermingled with horse droppings, and unsavoury morsels such as cabbage leaves, and gutter rubbish. Boots and shoes became badly soiled men wrapped sheets of newspaper around their legs below the knee, and the womenfolk were compelled to raise their full length skirts to at least ankle height, which to the more fastidious, was a most embarrassing procedure.

It is more than passing strange to note how little the architectural features of the two-storied shop buildings at Kogarah have changed over the years. The elimination of kerbside verandah posts has resulted in the removal of overhead balconies, which were a feature of the 1880s shop design. The access doorways to these balconies were partly blocked up, the upper sections being fitted with sash windows of narrow width. Many of the old verandah posts were provided with steel hooks and rings, placed at a height of about five feet above the kerb, to which the reins of horse harness could be attached as a safety measure. Horses often became fractious and inclined to bolt when a passing steam locomotive, or steam tram motor on the Sans Souci Tramway across the road, gave vent to an imperious blast on its steam-operated whistle.

The Bank of Australasia was first established in the two-storied premises standing at the north-western corner of Rocky Point Road and Hogben Street in what may be regarded as “Old” Kogarah. With the advent of the railway a move was made to “New” Kogarah where the Bank occupied the two-storied premises sited at the western corner of Montgomery Street and Railway Parade. A further move was made about 1905 when the vacated building was taken over by a newsagent named J.H. Harrison. The footpath against the front windows now became lined with poster boards advertising the various daily newspapers and the weekly journals. The windows displayed a wide range of school requisites together with writing pads with garish covers, stationery, pencils, penny bottles of inks of various colours black, blue-black, red, purple and green, and penny bottles of adhesive gum. There were coloured chalks in small cardboard boxes, slates and slate pencils, and tin boxes of water-colour paints which were ideal for the junior artist and his colouring picture books. The interior of the shop was fitted with a full length counter featuring numerous piles of newspapers, whilst a range of shelves behind the counter was given over to the storage of the hundred and one items of saleable stock. There were racks of highly coloured postcards, then in great demand, and which now form collectors’ articles, particularly those cards depicting sugary love scenes amidst an abundance of pink and blue tinsel and forget-me-not flowers. It was, and still is, a fascinating shop and the variety of the stock-in-trade has not changed overmuch, although slates and slate-pencils are missing from today’s school curriculum.

Next door was the butchers shop conducted by Mr. A. Rollings, an old resident of Kogarah, who also owned a livery stable located at the school corner of Regent Street and Gladstone Street. This shop was of modern type with its front enclosed by a large plate-glass window. In later years this particular window was distinguished by a water-spray arrangement placed inside along the top edge, enabling a film of water to trickle over the glass, thus giving an impression of coolth to the platters of meat arranged within. Festoons of meat and also pork sausages hung from hooks fastened to rails fixed beneath the ceiling of the window enclosure, together with sides of mutton and lamb. Sprays of bush fern and an odd lemon or two served as a garnish for the tasty exhibits. The prices then charged for meat would make a present day housewife gasp. Sides of mutton were sold at 1 3/4d. per pound, whole loin at 2 1/2d. per pound, legs at 2 3/4d. per pound, whilst beef was just as cheap. Chuck steak cost 3 1/2d, per pound, rump steak 6 1/2d. per pound, fillet steak 7d, per pound, and round went at 4d. per pound. One could also buy 100 pounds of corn beef at 17 shillings and sixpence.

Inside the butcher’s shop was a floor covering of sawdust and hanging from overhead meat-rails were sides of beef, clumps of livers, hearts, etc. , and sheeps’ heads in clusters, together with a range of lamb and mutton carcasses. The meat portions were dismembered on large wooden blocks cut from the trunks of trees specially for that purpose. A special table, with raised tray-like sides, served to contain the salt-port and salt brisket pieces, usually done up in rolled sections and fastened with wooden skewers, thus being ready for the cooking pot. Weighing was done on suspended scales fitted with a “clock” face and careful housewives closely watched to see that the weight of the butcher’s hand was not included in their purchase, a practice somewhat common to butchers’ shops at the period under review.

Then came the tobacconist and hairdresser’s shop operated by Mr. A. Davis, with its front verandah poles painted in alternative red and white stripes, a trade sign of old denoting red blood and white bandages, relating to the period when barbers also officiated as surgeons. Plug tobacco was in great demand by pipe smokers, who were legion, and Havelock or Yankee Doodle were the popular brands, Capstan cigarettes, at ten for threepence, found a ready sale amongst the younger generation, each packet containing two or three waxed paper holders in addition to a cigarette card giving a coloured representation of topical events or illustrating animals, birds, flowers and so on and so forth, such cards are eagerly sought today by collectors of such bric-a-brac. “Winifred” cigarettes, a hard-packed variety, came from England and sold at six-pence per packet of ten, whilst Turkish cigarettes, an acquired taste, were also procurable, together with choice Havana cigars. Haircut styles were generally short back and sides and shaving, shampooing and beard and moustache trimming were the order of the day. Regular customers were privileged to have their own shaving mugs and brushes, kept in a narrow glass-faced wall cupboard, retained for their own special use. The ladies of the day gloried in their long hair and had little if any use for professional hairdressers.

The next shop westwards was formerly occupied by Mr. F. Leathart as a newsagency, but in 1908 the premises became a fruit and vegetable mart under the jurisdiction of Mr. C.E. Hitches. The single display window was devoted to fruit in season, neatly arranged in stacked fashion whilst the vegetables were placed in tilted fruit-boxes lined against the wall on the customer side of the counter. One of the specialities of the shop was the supply of soup vegetables, when a carrot, a parsnip, a turnip, a sprig of parsley and a portion of a stick of celery, wrapped in newspaper, was sold for one penny. Soft drinks, in glass bottles, fitted with wooden screwed stoppers, were supplied by Messrs. Marchants and retailed at twopence each, a half-penny being paid to the customer for the return of the empty bottle. A special feature of the place was the overhead suspension of strings of pineapples, both in the window and above the counter, each tied by a separate piece of string, thus enabling the customers to make their choice as to size and degree of ripeness.

Then came a ham and beef shop, nowadays called a delicatessen, under the ownership of Mr. A. Bowman but later presided over by Mr. & Mrs. Potts. If our memory is correct, Mr. Potts worked in the Railway Department and only appeared behind the shop counter in what we may call his leisure moments. He was gruff in his manner to the customers and on one occasion a young girl visitor from South Australia asked for “threepenneth of ham cut thin”, Mr. Potts raised his eyebrows and replied “Yer don’t think I’d cut it in junks do yer?”

Most of the commodities for sale were kept in the front window, at the back of which was an arrangement of sliding doors screened with wire mesh to keep away the all-pervading flies. The leg of ham reclined in a place of honour atop a chaste white circular shaped porcelain stand, the smaller portion of the ham being encased in a white paper collar with scissor-cut fringe at the outer edge. The large piece of cooked corn beef was kept on a huge meat dish embellished with a floral design. Strings of red coloured polony, a partly cooked pork sausage, were draped across the window at times, whilst German Sausage in lengths of about two feet and some five inches in diameter, graced another large plate. Extra plates were also devoted to penny saveloys and Black, and also White puddings, a somewhat tasteless sausade made, so it is believed, from the 124 blood of pigs. At the advent of the First World War, for patriotic reasons, the name of German Sausage was changed to London Sausage and later to Devon, under which name this lunch favourite is still known. Pickled cucumbers of sickly hue were in demand whilst roast sucking pig, suitably seasoned and garnished with parsley, with a half lemon placed within the leering mouth, occasionally appeared in the window, the piglet being sold, usually, in quarter pound lots. A good aroma was emitted by several lengths of garlic and other highly seasoned sausages.

A portion of the front window was set aside for cakes, the centrepiece of which was a squarish shaped block cake from which portions were cut to suit the customers requirements. The smaller cakes, usually selling at a penny each, comprised Sponge Fingers, oblong in shape lightly dusted with icing sugar, jam and also lemon-cheese tarts, Chester Cake filled with stale cake crumbs mixed with currants and held together with jam or some such sticky substance, the whole being placed between two wafers of sterner pastry material. These were great favourites. There were also pink and white iced Fairy Cakes, some three inches in diameter and about one inch in thickness, the edges being tapered to a central point. A small portable oven, heated by a spirit burner, was placed on the counter, a device which kept the meat and the pork pies hot, or should we say, lukewarm. The meat pies, rather flat with flaky brown tops, retailed at one penny each, while the Pork Pies had a depth of about two inches and a diameter of five inches, and sold at twopence each. There was always a doubt as to the quantity of pork used in their manufacture, but there was never a doubt about the hardness of their ‘boiling water” pastry. The stock in trade was always on the sparse side as refrigeration of any kind was not available locally and a quick turnover was necessary to avoid trading losses.

Cream in jars and bulk milk were also retailed, the latter being kept in a lidded churn and ladled into the customers’ jugs per medium of a half pint measure, attached at the end of a long handle with a bent hook at the upper end. On one well remembered occasion, as a child, I asked for “a penneth of cow’s milk”, getting the surly answer, “Yer don’t think we keep goat’s milk do yer”. Incidentally, if one did require goats’ milk, which was in slight demand at the time for ailing persons and young babies on account of its richness, a supply could be obtained from a lady who kept a large flock of goats at her residence in the eastern section of Warialda Street, West Kogarah.

The general store, believed to be the first shop erected in the immediate vicinity of the Kogarah Railway Station, conducted by Charlie Barsby, J. P. , was a universal emporium catering for the softgoods and hardware needs of the local community, Charlie Barsby was a well known identity of the St,George District and at the mention of his name one recalls a huge gum tree growing in Skidmore’s Paddock, near Muddy Creek west of the Rocky Point Road bridge In the upper branches of this then lone tree was a large wooden sign-‘board which read; “Woodman spare this tree in memory of poor old Charlie Barsey”. As usual the tree wasn’t spared but one often wondered as to the “whys and wherefors” of this particular board.

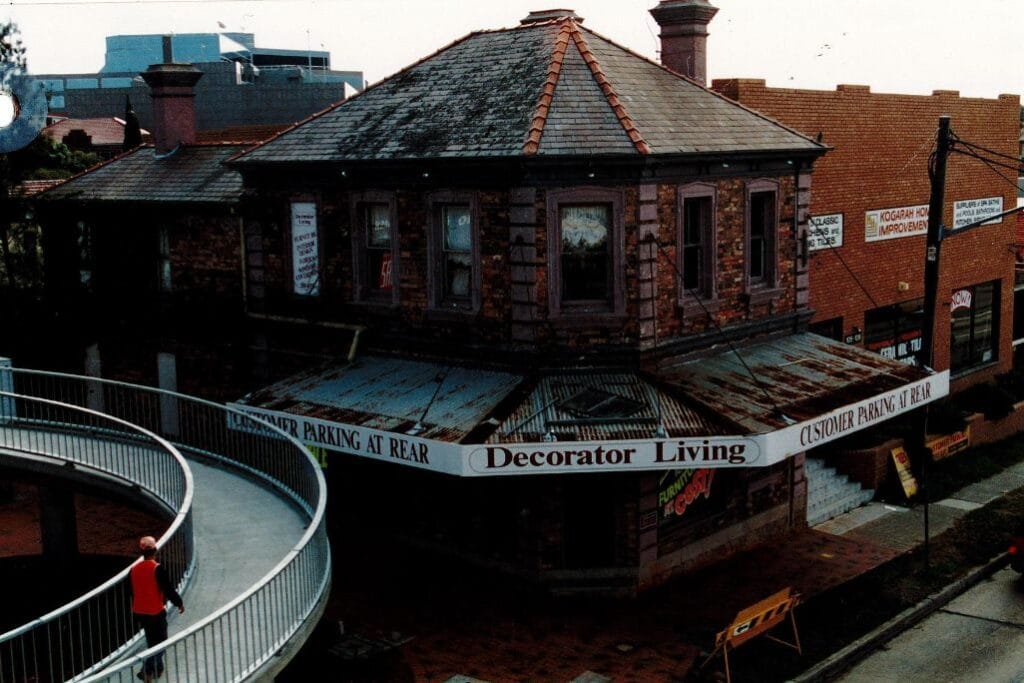

Charlie Barsby’s store was triangular shaped and covered two divisions, separated by a brick wall and having an interconnecting internal doorway. The eastern section of the premises were devoted to all manner of millinery, dress materials, manchester, haberdashery and such like merchandise, presided over by a capable lady named Miss Soutar. A set of stairs at the far end of the store led to an annexe which was top-lighted by a glazed panel set in the roof.

The several wooden counters were lined with bentwood chairs, the cane seats of which were small in diameter and too high for the matronly figure to be really comfortable. Full length mirrors were placed here and there for the benefit of customers when trying hats for style, shape, and size. The inner mellow daylight of the store made it necessary to adjourn to the outside footpath when matching the colours of ribbons, or materials, the customer being accompanied by a member of the sales staff. The dark counters had their top inner edge inlaid with brass yard measures to which the length of materials were applied before being snipped with the shears. Sheets of tissue and also brown paper were kept ready for use beneath the counter and balls of string, contained in a round perforated cast-iron cage, dangled overhead at the end of a cord attached to the ceiling. One recalls the pallid-faced shop assistants, dressed in regulation black, their skirts sweeping the floor and the front of their blouses stuck about with pins, a tape measure being draped around their necks ready for instant use.

For a mechanically minded boy the greatest fascination of Charlie Barsby’s store was the cash railway, an overhead structure of polished wooden slats which sloped from a high level gradually to a centrally located elevated cashiers cubicle. A second similar wooden track, sloping downhill so to speak, ran from the cashiers cubicle to the receiving and dispatching depot mounted on the wall at the rear of the counter. There were several of these installations leading from and to the various departments of the store. After the sale had been made the shop assistant placed the docket and the money tendered in a wooden ball, about five inches in diameter and so constructed that its two equal sized sections could be screwed together by a turn of the wrist. This ball was then placed in a lifting cradle and raised by a cord to the high-level slatted track, here a trip device sent the ball rolling on its way until it landed with a plop in front of the lady cashier. The docket, and any change money, was placed in the ball for the return journey, via the slotted track at the lower level. The ball made its final descent to counter level through a circular shaped string webbing which served to break the velocity of its fall. This cash railway was a most ingenious device which belonged to the days before American cash registers came into common use at each counter.

The southern section of the general store was given over to groceries and household hardware. Here the tea and sugar, together with the thousand and one items of culinary import, were sold by old and young gentlemen, each wearing a long white apron attached at waist level and a stub of pencil tucked behind one ear. The chief salesman was a rubicund portly and kindly man named John Adams, who later went into the grocery business on his account further south along Railway Parade, Near the door of this section of Charlie Barsby’s store was the allotted place for buckets, brooms, mops and feather dusters, all intermixed with a great variety of crockery and pots and pans. There mere jelly moulds, patty-tins, cake-tins, oven dishes and colanders, sited amongst oil-lamps of glass and shiny candlesticks of brass. A wondrous assortment of goods, most of which would be museum specimens today.

The long established general store of Charlie Barsby was taken over about 1906 by Walter Turner and it was not long before the grocery and hardware section was discontinued and replaced by a department devoted to the sale of men’s wear. The business still functions under the name of Turner Brothers.

The section of Railway Parade between Montgomery Street and Charlie Barsby’s corner could be described as the main business centre of Kogarah. Here the Kogarah Municipal Band played on Saturday night late shopping period, and it was also the gathering place of the local “push” of those days. Possessed of knuckle-dusters the gangs made their fun by jostling and forcing people, irrespective of age, sex, or physical handicap, from the footpath to the murk of the roadway. A “Cockatoo” stood at the corner of Montgomery Street to keep a wary eye on any approaching policeman. Clashes and brawls with other visiting pushes were frequent and generally finished up as street riots, to the detriment of householders’ picket fences, the palings being handy as weapons. Members of this pea-brained mob have ,been known to tear up stones from the roadway and smash the windows of those persons unfortunate enough to incur their displeasure.

On the western side of Railway Parade was an avenue of trees, beneath which stood a ten-passenger “sociable” coach, drawn by a pair of horses, which plied between Kogarah Station and Sylvania. Entrance was gained to this vehicle by a series of steps placed at the rear doorway. The Hansom-cab, presided over by Mr. Goodsell, was also available for hire in this vicinity. About 1908 the Sans Souci Tramway had a portion of its “Up” line laid along the length of Montgomery Street in order to obviate the need of “Up” trams to Kogarah climbing the steep Gray Street hill, The trams often discharged their passengers at the “Papershop Corner”, prior to rounding the sharp curve which reversed their direction ready for the outgoing journey. At this time the “Dock” tramway platform, against the “Down” railway platform; at Kogarah Station, fell into disuse, apart from providing standage for coal trucks.

On the southern side of Charlie Barsby’s store stands the Railway Parade Hotel, later renamed Railway Hotel and now known as Kogarah Hotel. This building was taken over, before its completion, by Mr. W.F.J. Stroud, who, after many years as licensee, was succeeded by Mr. Henderson, who in turn was followed by many other publicans. At the period under review, draught beer was sold at the bar for threepence a pint, consequently there was a great deal of drunkenness. Next door was a primitive weatherboard shop where half cases of fruit were ranged along the side walls, under the watchful eye of Miss Amy Tatler. This lady specialised in selling ripe and luscious figs in season. The premises were subsequently demolished and replaced by Mr. Emerick’s boot and shoe shop, which was centrally divided by a long double seat, having a common back, which enabled the sexes to be suitably segregated when being fitted with footwear. Mr. Emerick advertised “If the tongue of this boot could speak it would say: Go to Emericks for your boots.”

Then came the chemist shop of Mr. S.A. Casson, distinguished by a window display of two huge onion-shaped apothecary glass bottles, one containing, if our memory is right, red coloured liquid and the other blue. Rows of shelves, enclosed with glass doors, lined the side and end walls and were stacked with all manner of patent medicines and remedies, while a large section of the northern shelves contained numerous square- shaped glass-stoppered bottles, each with the name of the contents exhibited in black lettering on a ground-glass background. Against the long counter was a set of scales devoted to the weighing of babies, a courtesy extended by the management. The staff wore three-quarter length white coats, and there was a distinctive range of smells emanating from the dispensing department at the rear of the shop. Then came the hairdressing establishment of Walter Harris.

Next door was the high class fruit and confectionery shop kept by Mrs. G. Ashman which did a great trade with visitors making their way to the St. George Cottage Hospital at Kogarah. The single window displayed orderly arrangements of fruit in season. Against the wall behind the counter were shelves devoted to square-shaped glass jars containing numerous varieties of sweets which were retailed in ounce units per medium of dainty brass scales. Fancy boxes of chocolates, each tied with either a red, green, yellow or blue ribbon, and depicting some pleasant mountain scene or arrangement of flowers, made a delectable if expensive showing. There was also a wide range of screw-topped bottles containing Marchant’s ginger-beer and lemonade, together with Starkeys “Stone” ginger-beer contained in white porcelain bottles, the corks of which were kept in position by wire knotting. Another glistening feature of the soft-drink shelves were the rows of “Codd” bottles which were stoppered internally by a glass marble, kept in place by the pressure exerted by the carbonic acid used as an effervescent for the lemonade contents. These bottles often came into the hands of boys who promptly smashed them to obtain the coveted glass marble. Soda water siphon bottles held a place of honour and were in demand for hospital patients in particular. One pleasant memory of Ashman’s shop is the special aroma, which was delicious to say the least, as it arose wholly and solely from the large quantities of ripe and ripening fruit contained within the open-backed front window.

Next door was Mrs. I. M. Reid, milliner, and in order, stationery shop of Arthur Quartley, followed by Frederick Hartley, undertaker, Mr. S.W. Lowers pharmacy, and the grocery shop of J. G. Lockington. These several shops south of the hotel were two-storied with balconies overhanging the footpath. At the northern corner of Railway Parade and Belgrave Street was Kogarah’s ornate post office, a distinctive two-storied building with a pointed roofed tower representing the “Norman” architectural period.

The rerouted track of the Sans Souci Steam Tramway, in the outward direction, passed alongside the western footpath of Railway Parade from the Railway Station until it reached a point opposite the intersection of Belgrave Street. Here it curved to enter a gateway to join its original track, passing by a rather ugly wooden coal stage, dominated by elevated water-tanks. Beyond, in a southerly direction, and contained within the railway boundary fence, was a long and lofty single tracked tramcar shed constructed of galvanised iron. Tram vehicles underwent minor repair and brake adjustments within this shelter. This section of the tramway was always very busy traffic-wise., with steam motors being serviced, coal trucks unloaded, and outward bound trams tootling by at regular intervals. There was always plenty of whistling, plenty of ash smuts,, and plenty of coal smoke from these delightful and sturdy old steam horses.

South of the Belgrave Street intersection and set well back from their frontage to Railway Parade, was a terraced group of three single-storied white-washed cottages, each front garden surrounded by a low white-painted picket fence. The end-gabled roof, if our memory is correct, was common in length to all three units, John Tait, a house-agent lived in the first, Emma Hurry in the second, and Mrs, Jane Ridley in the third. Then came a small weatherboard shop, a two-storied double fronted shop, and also the printing office of David Christian and Company. Louisa Spencer had a confectionery business and Mr J. W. Tidmarsh (next door), a house and land agency. A single-storied weatherboard shop housed Mr. J. Lawrence who specialised in making and repairing all manner of boots and shoes. His workshop employed eight skilled hands on a full-time basis. A row of small cottages, mostly single-fronted (which later had shop fronts added) extended side by side to reach the bakery of Mr. A. Brett, after which came a pair of two-storied brick shops, the first being the fruit shop of Miss M. Hitches, and the second, located at the northern corner of the Derby Street intersection, was occupied by Messrs. W. Peatfield and Son, a firm of ironmongers, painters and interior decorators.

From the Derby Street intersection towards Gray Street was a further row of cottages. About 1908 Mr. Tom Baldwin, a butcher from Riverstone Meatworks, opened a retail shop which is carried on today by his two sons. At the northern corner of Gray Street was, and still is, a fruit shop which has seen many calamitous happenings to its footpath awning and verandah posts. In the vicinity of this particular shop the Sans Souci Tramway curved sharply from the railway enclosure, crossed Railway Parade on the level, skirted the gutter in front of the shop by inches, and climbed its curvaceous way into Gray Street, The steep grade had to be taken at speed, with the steam motor whistling continuously for the right of way (said whistles could be heard at distant Arncliffe, they were so intense and loud). On occasion an imprudent motorist, unaware of the habits of the tram, would decide to race the wildly shrieking tram motor and was bewildered when the tram crossed his path, forcing him to make one of two choices – either to crash into the side of the fast moving tram, or to bring the shop verandah posts and awning down to footpath level, The latter choice was invariably made, much to the annoyance of the excited occupier of the fruit shop.

At this juncture it is thought desirable to end our story of this section of the Kogarah shopping centre ranged along Railway Parade. We trust that it will enable the members of our society to draw comparisons of the scene today with the conditions which appertained to yesteryear.

This article was first published in the October 1971 edition of our magazine.

Browse the magazine archive.