by Alderman R. W. Rathbone

Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney, came of an old and very distinguished Norfolk family who are still resident at the family seat, Raynham Hall, near the quaint Tudor market town of Fakenham. They first settled in the area in the early 15th Century and, with the exception of several years during the period of the Commonwealth when their lands were confiscated because of their Royalist sympathies, they have remained in this area ever since.

The first member of the family to come into prominence was Sir Roger Townshend, who sat in the House of Commons as M.P. for Calne in Wiltshire where the family also held large holdings. He was a lawyer of great eminence who was made the King’s Sergeant at Law in 1483, Judge of the Court of Common Pleas in 1484 and was knighted by King Richard III in 1485. He married Eleanor Lunsford of Battle in Sussex who was related to the Sidney’s of Penshurst whose descendant, Viscount de L’Isle and Dudley was one of the last British born Governor’s General of Australia. Through her the family also acquired large estates in the County of Sussex.

There were three sons and three daughters of this marriage, the eldest of whom, also named Roger, succeeded his father as M.P. for Calne In 1493. He, too, had three sons. Robert, the eldest, followed his grandfather to become a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas and the second Chief Justice of Chester. Robert and his son, Richard both predeceased their father and grandfather who lived to the quite incredible age in those days of 94 and Roger Townshend was succeeded by his grandson, also called Roger.

This Roger Townshend succeeded to the family estates in 1551 and was knighted in 1588 on the recommendation of Charles, Lord Effingham, Lord High Admiral of England, for his spirited conduct against the Spanish Armada. His eldest son, John, who was M.P. for Norfolk also fought against the Spaniards and he, too, received a knighthood after the memorable Siege of Cadiz in 1596.

Sir John Townshend had two sons, John who was killed in a duel in 1603 and Roger, who succeeded him as the first baronet. This Sir Roger Townshend was M.P. for Oxford and later for Norfolk. His son, the second baronet, died childless and the title passed Li his younger brother, Horatio. Horatio was an avowed Monarchist, fought for and stood loyally beside Charles I during the Civil War and was stripped of both his title and his estates by the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. After the restoration of the Monarchy in 1661, however, he not only had his estates returned but for his loyalty to the King’s cause, was raised to the rank of a baron and in 1662, advanced to the dignity of a Viscount, Taking the title Viscount Townshend of Raynham.

Like so many of his predecessors, he also had three sons. The eldest, Charles, who succeeded him as the second Viscount, had a long and distinguished parliamentary career. He was Lord Lieutenant of Norfolk, Britain’s Ambassador at The Hague and one of the Regents of the Realm during the Reign of George I. This last position was no sinecure for, during the reign of the first George, George spent much of his time out of England in his other Kingdom of Hanover and was the only British Monarch for over a thousand years not to be buried somewhere in England.

He held continual office as Secretary of State under George I and George II from 1714 to 1730 and was made a Knight of the Garter for his services. While Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s first Prime Minister, concentrated on the country’s domestic affairs, Townshend directed its Foreign Policy almost uninterrupted for nearly twenty years during which time he kept Britain at peace with its traditional enemies, the French, the Dutch and the Spaniards. His relations with the French were, in fact, too close for Walpole’s liking and in spite of the fact that he was Walpole’s brother-in-law, he was forced from office in 1730.

He then retired to his estates where he spent his final years experimenting with large scale turnip cultivation and the four course rotation of crops – a year of cereals, a year of legumes, a year of root crops and the fourth year fallow. Turnips up until that time had been cultivated only as a source of stock fodder and particularly as feed for pigs. Townshend espoused their health and medicinal properties and alone was responsible for their acceptance as food fit for human consumption. This earned him the nickname of “Turnip Townshend” by which he is best remembered whilst his considerable achievements as a Statesman are almost totally forgotten.

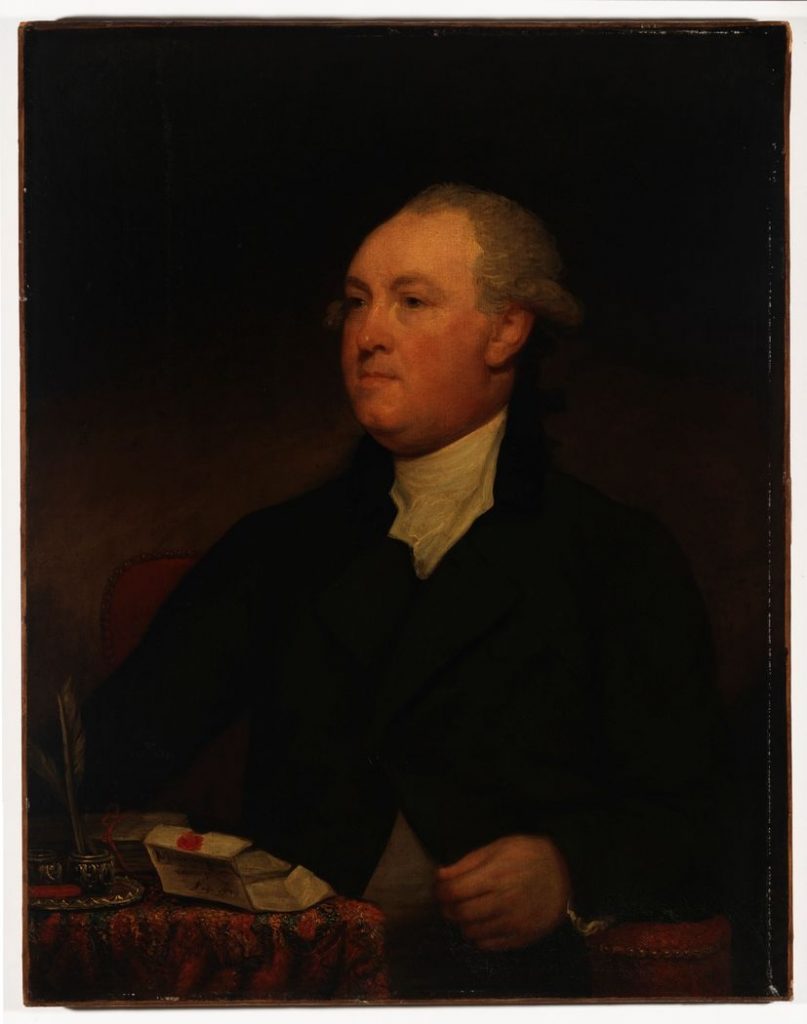

Charles Townshend had two sons, Charles the younger, who succeeded to the Title on his father’s death in 1738 and Thomas, who, apart from being M.P. for Cambridge, was an acknowledged Classical Scholar. He was born in 1701 and married in 1730, Albinia Selwyn, daughter of Colonel John Selwyn of Gloucestershire who, on 24th February 1733, presented him with a son and heir who was also baptised Thomas and is the gentleman about whom this story is set.

History has judged this man very harshly claiming that he possessed neither the intellect of his distinguished father nor the political perspicacity of his illustrious grandfather. He was educated at Eton College and attended Clare College at Cambridge where he succeeded in obtaining his Masters Degree in 1753. On 17th April 1754, at the age of 21, he was elected to the House of Commons for the pocket borough of Whitchurch in Hampshire where the family also held large estates and remained Member for that constituency for the next 29 years. For twenty of those years, he had the unusual distinction of sharing a place in parliament with his father who represented the Cambridge University seat until 1774.

A dissolute and a philanderer in his youth, he was known as “Tommy Townshend” but on 19th May 1760, he was married off to Elizabeth Powys, a tough and resourceful Suffolk heiress who smartly pulled him into line and apparently managed to keep him in the marital bed for she presented him with no less than twelve children, six boys and six girls over the succeeding fifteen years.

In 1756, he was appointed Clerk of the Household of the Prince of Les, a sinecure that ensured the Prince was aware of Government [icy on major issues of the day and sufficiently intimidated not to express opinions contrary to those of the governing political party and, the accession of the Prince of Wales to become King George III, he was appointed Clerk of the Board of Green Cloth, another sinecure designed to see that the King was always aware of how he was expected to react to any sudden changes in Government Policy. He was greatly influenced by his Great Uncle, the powerful Duke of Newcastle and vigorously opposed the expulsion of John Wilkes M.P. for Aylesbury from the House of Commons when he refused to withdraw his criticism of the King’s Speech from the Throne, was convicted of libel and accused of being a member of the Hell-Fire Club which held satanistic orgies at High Wycombe.

He also opposed Lord Grenville’s Stamp Act which imposed severe taxes on the American colonists and ultimately led to the War of American Independence declaring passionately that Grenville was treating the Americans with “levity and insult” and, with the outbreak of civil disobedience in the Americas in 1765, he fought the Committee Stages of the America Mutiny Bill clause by clause. His fierce loyalty to the King also saw him lead the opposition to the Regency Bill when the King was declared insane and incapable of carrying out his functions as Monarch. When offered a position at the Treasury in the administration of Lord Rockingham, he refused it unless William Pitt was also included in the Ministry and when Pitt declined to serve under Rockingham, was responsible for Rockingham’s resignation to make way for Pitt.

In 1765 at the age of 32 he became a Lord of the Treasury under his cousin, Charles and was a contemporary and friend of the greet orator, Edmund Burke. He was advanced to the position of Joint Paymaster of the Forces and held that office until 1768. Without commanding talents or brilliant eloquence, he appears to have been an honest and capable administrator and if he had no other attributes, he displayed an honourable consistency and loyalty during a period of great public corruption and dishonesty. In 1767 he was made a Member of the Privy Council but resigned all offices in 1768 when he was passed over for the position of Paymaster General.

He was an unapologetic Whig, i.e. a Liberal, and was out of office throughout the Tory Conservative ascendancy of Lord North between 1770 and 1780. During these ten years he was a particular critic of the Tory Government’s American policy urging conciliation and appeasement at every turn and strongly opposed the Tea Duty which he described as “frivolous and unnecessary” and which proved to be the spark which set the American War of Independence alight in 1775. Throughout the course of the War he was second only to the great orators, Charles James Fox and Edmund Burke in his condemnation of the conduct of the hostilities.

It was said of him that his abilities, though respectable, scarcely rose above mediocrity, yet he always spoke with facility, sometimes with energy and was never embarrassed by any degree of timidity and he maintained a conspicuous place in the front ranks of the Opposition. In 1769, Burke had said of him -“Had there been fuel enough of matter to feed that man’s fire, it would make a dreadful conflagration”. During the War of American Independence there was no lack of material and he habitually reproached the Government in the harshest language.

Perhaps it was unfortunate that he was constantly overshadowed by his more brilliant cousin, Charles Townshend, who was noted for his powerful oratory, masterful personality and shameful inconsistency. It was said that Charles Townshend lacked everything that was common common truth, common honesty, common sincerity, common steadiness and common sense ….. and it was only after his death at the age of 42 in 1767, that the true qualities of his less spectacular relative came to be appreciated. In 1770 he was proposed as Speaker of the House of Commons but declined the nomination.

The War of American Independence concluded in 1781 with Britain’s most ignominious defeat in its history and shortly after the Conservative Administration of Lord North fell. Rockingham again became Prime Minister and Thomas Townshend was appointed Secretary of State for War. To him devolved the responsibility of concluding the War and of representing Britain at the subsequent Treaty of Versailles. His conciliatory attitude to the Americans ensured that any animosity between the two proponents was kept to a minimum and above all else, his handling of the negotiations resulted in there being no lingering legacy of bitterness over the conflict. To him must go the credit for the special relationship that has existed ever since between the two leading English speaking nations of the world.

He also proved to be a master at out-manoeuvring America’s allies, the French and the Spanish who received few rewards for their support. The Peace, he said, was as good as Britain had the right to expect and a Peace that promised to be permanent. He belittled the concessions Britain had to make to France and Spain and declared that Britain should continue to consider the Americans as their brethren and give them as little reason as possible to feel they were still not British subjects.

So pleased was the Government with what he had been able to salvage from the War and his masterful handling of the Peace negotiations that in 1783 he was translated to the House of Lords with the title of Baron Sydney of Chislehurst. It is thought he took the name Sydney from his relatives, the Sydney’s (Sidney’s) of Penshurst, previously mentioned.

On 22nd January 1784, he was appointed Secretary of State for the Home Department which dealt with Colonial Affairs, a position he was to hold for the next five years when he was elevated to the title of Viscount Sydney of St. Leonards in the County of Gloucester.

The greatest single task that confronted him in his new portfolio was not what to do with Britain’s overcrowded jails and the stinking hulks which accommodated their overflow, as most Australian historians have suggested, but what to do with the 15,000 American loyalists of British origin who had returned to Britain after the War of American Independence. These settlers had lost everything because of the British Government’s bungling of the War and they demanded resettlement in some other part of Britain’s growing colonial empire.

Their leader was James Mario Matra who, despite his Corsican ancestry was actually an Englishman of Irish extraction who had been born in New York and educated in England. He had accompanied Captain Cook as a mid-shipman aboard the Endeavour and on his return to England was appointed British Consul in Teneriffe and later, Secretary of the British Embassy in Constantinople. In 1783 he returned to London where he soon became recognised as the leader of the American Loyalists resident in Britain.

Having sailed with Cook to Australia and having maintained a long-term friendship with Sir Joseph Banks, Matra was well aware of the potential for settlement there and in August 1783, he submitted to Lord Sydney, a proposition to resettle the American loyalists in N.S.W. he Government, however, had other priorities, not the least of which was he rebuilding of the British Navy which had been allowed to run down under the previous administration and had proved largely ineffective in the war with America.

Sydney at first showed little interest in the project until it was pointed out to him the country’s enormous potential for the growing of flax, a commodity much needed for the manufacture of ships’ sails and one that was in chronic short supply now that America had won its independence. Flax could also be made into hemp for rope and as Britain’s main supplies of this material came from Continental Europe, its availability was always at risk.

Matra tried again. This time his proposition was not only to resettle the loyalists in N.S.W. to grow flax but also to solve the problem of England’s overcrowded jails by sending the convicts to work as indenture servants under them. He finally won Sydney’s interest when he mentioned the huge stands of timber that lined the eastern seaboard of N.S.W.. Timber for rebuilding the Navy was also in short supply.

These factors, together with concern at France’s interest in the South Pacific following the expeditions of Count Jean de La Perouse, caused Sydney to reconsider his initial disdain of Matra’s proposals and by May 1785, a plan had been formulated which encompassed nearly all of Matra’s suggestions. By this time, however, most of the loyalists, tired of waiting for the Government to decide their future, had returned to North America and settled in Nova Scotia. They apparently bore Sydney no ill will as they named the capital of their settlement, Sydney, after him.

As they were now no longer a consideration in Sydney’s deliberations, he decided to press ahead with a settlement in N.S.W. composed largely of convicts. Despite what some historians would have us believe, there Is no evidence that ridding Britain’s jails of their convict inhabitants was a major priority of the British Government at the time. These unfortunates had long been a handy source of cheap labour which was used extensively on public works projects such as dredging sand and silt to keep Britain’s ports accessible to the sea. Only an outbreak of disease on the insanitary hulks in 1783 had caused the re-settlement of their occupants to even be a consideration. In any case, the Government was more inclined to send them to Canada or the West Coast of Africa. The plan put forward by Matra was placed before Lord Sydney in January 1785 and adopted by the Government early the next year.

Present day historians are quick to condemn the convict system and Britain’s sponsorship of it and there is no doubt that in many of its aspects it was a cruel and degrading system but by the standards of its day, it was the most enlightened form of penal administration the world had ever seen. Other European countries simply hanged their criminal classes in vast numbers or used them in chained gangs in their mines, galleys and quarries and other places considered totally unsuited for any creatures other than animals. The British convict system with its limited sentences and remissions for good behaviour was the first penal system in the world which offered its participants any hope of rehabilitation and release.

On 18th August 1786, Sydney wrote to the Lords of the Treasury asking that an adequate provision be made, a proper number of vessels be made available to conduct the convicts to their destination and two Naval vessels be provided to escort them.

It was the prerogative of Lord Howe, First Lord of the Admiralty, Britain’s most distinguished naval officer, an able administrator and a man of immense personal prestige, to decide who should command the expedition but Sydney made It quite clear to Howe that the man he believed had the capacity for the task was Captain Arthur Phillip. Not only did Howe resent this usurping of his authority but he stated quite categorically that he did not think Phillip had the qualities for the task that were required. Phillip was well known to Sydney as the vast Townshend estates in Hampshire adjoined the modest estate at Lyndhurst owned by Phillip. It Is not generally realised that Phillip was also accomplished farmer as well as being a competent and successful naval officer.

Sydney was often criticised during his years in office as being insensitive and a poor judge of men, but he could also be a very determined man and backed by Sir George Rose, Treasurer of the Navy, who also lived near Phillip, he stood his ground against the opposition of Lord Howe. His selection of Arthur Phillip was a stroke of genius.

Phillip was 48 years of age, short of stature and slight of build. His father had been a refugee Jewish language teacher from Frankfurt in Germany but his mother was the widow of Captain John Herbert of the Royal Navy. It was she who determined that her son’s career was to be that of a naval officer. Unfortunately for his mother’s ambitions, Phillip’s advent to the Navy coincided with the longest period of peace in Britain’s history and whilst he made steady progress through the ranks, he spent much of his time farming on his estate in Hampshire because there simply wasn’t anything else for him to do. He had a small, narrow face, a thin aquiline nose, full lips and a sharp, powerful voice. He was intelligent, active, kind but firm, lacking a sense of humour but above all else, intensely humane.

It is believed he accepted this comparatively mediocre assignment partly to satisfy his desire for adventure and his wish to command but mainly to get away from his wife, Margaret, who, from all accounts, was a harridan of the first order. He made meticulous preparations for the voyage ahead. No Australian historian has ever given this outstanding man his full due and it was significant that during our Bicentenary Celebrations in 1988, the exploits of this truly great man received hardly a mention.

No subject is more open to abuse and misinterpretation than history and few historians, particularly Australian ones, have ever let the facts interfere with a good story or justification for a cause. The facts of the Eureka Stockade, for example, bear little relationship to the popularly held concept of a heroic group of harassed and oppressed miners fighting for justice against corrupt authority. It is, in fact a sordid story of treachery, intrigue, cowardice and betrayal on a grand scale. The story of Ned Kelly is another but perhaps the worst distortion of all is the story that the degradation of the Australian aboriginal is due to the fact that a British Colonial settlement was established in Australia.

When Lord Sydney drew up his guidelines for the establishment of the settlement at Botany Bay, they contained detailed and specific instructions. After securing the company from any attacks by the natives Phillip was to proceed to the cultivation of the land. All convicts not needed in the production of food were to cultivate the flax plant. He was to grant full liberty of conscience and free exercise of all modes of religious worship not prohibited by law provided his charges were content with a quiet enjoyment of the same and he was to emancipate from their servitude any of the convicts who should, by their good conduct and disposition to industry, be deserving of favour and to grant them land, victual them for twelve months and equip them with such grain, cattle, sheep and hogs as might be proper and could be spared.

Nowhere were these instructions more specific than how Phillip was to treat the native inhabitants of the country. He was instructed to make contact with them, to establish and maintain friendly relations with them, to respect their culture and traditions and above all, to see that they were not ill-treated in any way. And he took these instructions very seriously indeed.

From the time he landed at Sydney Cove he interested himself in the life of the natives and did his utmost to win and keep their friendship. At first he seemed to have succeeded despite the fact that La Perouse had fired on them at Botany Bay and there were inevitable incidents between some of the convicts and the aboriginal women and there is no evidence that the aborigines resented the advent of the whiteman or that they tried to drive them out. They actually showed some admiration for their power and especially their leader whose missing front tooth apparently possessed some symbolic value. Even after he was wounded by a spear at Manly when one native misinterpreted his gesture of friendship as a hostile act, Phillip sought to maintain harmony while gradually persuading the aborigines of the superiority of the culture he brought with him.

Anyone who interfered with or ill-treated the natives during Phillip’s time in Australia was severely punished and he refused to allow retaliation against the natives when several of the convicts were speared when found in places they had been specifically instructed to avoid. The degradation and the ill-treatment of the aborigines dates from a much later period in our history and reached its peak when the discovery of gold brought to this country the very dregs of many nations motivated by greed and hell bent on exploiting everything it had to offer including its native inhabitants. Even Manning Clark, whose anti-British obsessions are well known, has had to admit Phillip treated the natives with the utmost kindness.

All that aside, it is doubtful if Phillip ever envisaged the settlement he established in Sydney Cove growing to a great metropolis of over three million inhabitants for whilst he certainly did name the bay on the shores of which the first convicts landed, Sydney Cove, after Lord Sydney he never at any stage named the settlement after his mentor. The name simply devolved from the bay on which it was set.

Shortly after the first reports on the establishment of the settlement at Sydney Cove reached London, in June 1789, Lord Sydney was forced out of office with a sinecure worth £2,500 a year and a viscountcy. He spoke only once more in the House of Lords in October 1789 then retired to his estates at Chislehurst in Kent. On 13th June 1800, Thomas Townshend, Viscount Sydney of St. Leonards in the County of Gloucester, died of apoplexy at the age of 67.

Of Australia’s six capital cities, Adelaide bears the name of a queen, Melbourne the name of a British Prime Minister, Brisbane the name of an early Governor and Perth, Hobart and Sydney the names of cabinet ministers. Is, then, Sydney, a worthy enough name for one of the world’s most beautifully sited cities?

Thomas Townshend has been described as a man without commanding talents or brilliant eloquence though he appears to have been an honest and capable administrator. In another age when he did not have to bear comparison with such historic figures as Charles James Fox, Edmund Burke and William Pitt, history may have been kinder to him. He was, at the very least, a good example of the noblesse oblige which served Britain so well over many centuries when men of wealth and privilege who had neither worldly goods nor prestige to gain, devoted their lives to the service of their country and to the betterment of their fellow man.

No biography has ever been written about him and no record of his achievements has ever been enshrined. He was, however, a man of peace and understanding and great humanity in an age when these qualities were often considered to be a sign of weakness. He was a capable negotiator, a conscientious public servant and a man of surprising strong will when the occasion demanded it.

And if there is no other reason why I believe he deserves our thanks and our honour, it was his choice of Arthur Phillip to establish the settlement In N.S.W. – a decision which ensured the success of this venture and the sound establishment of the nation we are all so proud to call our home today.

Based on information contained in the Mitchell Library of N.S.W., a biography of Arthur Phillip by Thea Stanley Hughes, the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Cassell’s Picturesque Australia, Records of the Library of the House of Commons particularly The History of the House of Commons 1754 -1790 kindly supplied by the Chief Librarian and family papers made available by George John, 7th Viscount Townshend of Raynham.

This article was first published in the May 1990 edition of our magazine.

Browse the magazine archive.