A Railway Is Built

Early in the 1860’s agitation commenced along the southern coastal district for improved means to transport the rich produce of the area to markets in Sydney. The small ships plying the coastal trade were both irregular and unreliable and the long, bad road was a nightmare. To ensure the development of the coal industry along the Illawarra coast, some speedy, efficient and reliable form of transport became necessary.

As a result of this agitation, added to the weight of economic factors, a number of trial surveys were begun in 1873 and continued for some years. It was intended to link the area with Sydney by means of a railway which was to cross Georges River by bridge and embankment at Rocky Point. This proved impossible owing to the difficulty in finding the bottom of the river. Successive governments baulked at the prospect of bridging rivers and constructing tracks on the sides of mountains and it was not until the late 1870’s that the scheme was finally tackled.

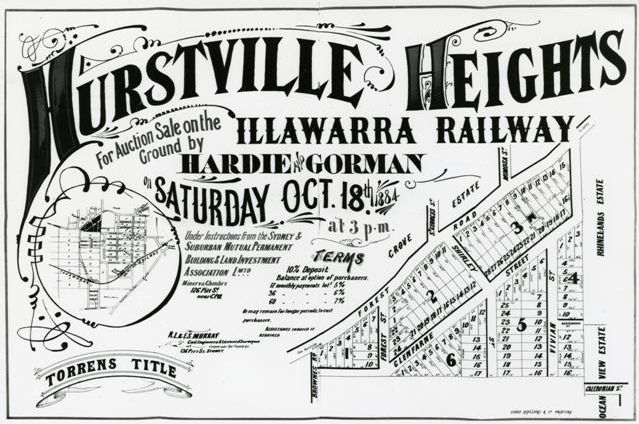

The Public Works Act of 1881 authorised the raising of £1,020,000 for the construction of the first section of the railway to Kiama. Tenders were called for the first portion in September, 1882. The date for completion as far as Hurstville was September 30, 1884.

Work commenced almost immediately and local residents soon had all doubts removed as to what route the railway would follow.

“The effect of the coming of the railway on the landholders of the district was electric. The people became land mad and the great land boom of the eighties got under way. Land values rose enormously and a steady influx of new purchasers became evident. Farms were either subdivided and sold in allotments or purchased by building societies for subdivision”.

Nowhere was this better exemplified than in the area upon which our story centres. Early in 1881, Alexander Milsop sold his orchard in Willison Road to John Cliff. The price paid, £2,565, was nearly five times what Milsop had bought it for only seven years before. In June the same year, Cliff sold the land to Dr. C. F. Fischer for £3,465. The following year it again changed hands for £5,850 when William Kingscote, a Tamworth farmer, bought it from Fischer.

Kingscote also purchased the adjoining 34 acres which had originally belonged to James Swaine but which had passed to Patrick McMahon and later to the Keane Brothers of Murrurrundi. The price paid for this land was £7,000.

With the railway already under construction, Kingscote sold his combined holdings to Robert Doyle on July 17, 1884 for the staggering price of £25,858 and only a few hours later it passed into the hands of the Enterprise Land and Building Company Ltd. for £27,535.

Thus, in the space of four years, land worth only a few hundred pounds became worth tens of thousands.

The Railway Is Opened

On Wednesday, October 15, 1884, the railway as far as Hurstville was declared open and a special train left Sydney at 10.30 a.m. carrying the Hon. F. A. Wright, Minister for Works, and party who deputised for Premier Alexander Stuart. Stuart had been laid low with a stroke, but sent his good wishes and an assurance that the work had been undertaken for the benefit of the Colony as a whole and not, despite libellous accusations to the contrary, because he owned considerable areas of land through which the line passed.

The stations along the line were decked with flags and floral displays, bands played, speeches were made, toasts were drunk, refreshments indulged in and a regatta held on the Georges River.

Local residents gave vent to their emotions by gathering in small knots along the track and vigorously waving their handkerchiefs in salutation as the official train passed.

Reporters spoke of beautiful undulating country with occasional glimpses of the water and the fading lines of dim hills which presented scenes of the most picturesque description.

A Municipality Is Born

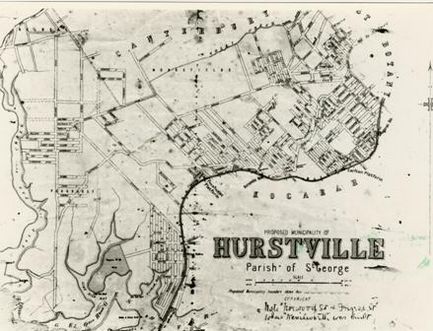

Soon after the opening of the Railway in 1884 moves were made for the incorporation of Hurstville as a municipal borough. Rockdale, or as it was then called, West Botany, had been incorporated as early as 1871. In 1885 Kogarah was granted municipal status.

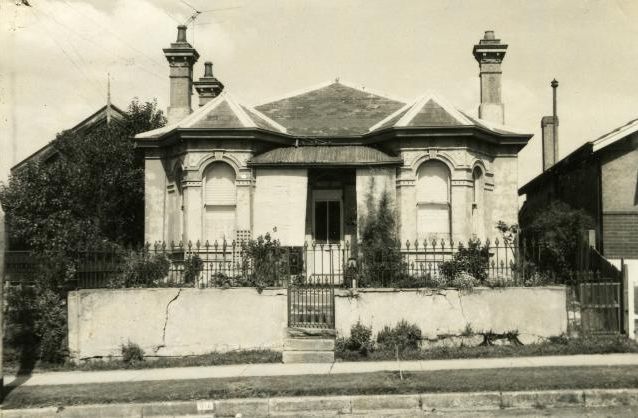

This prompted two prominent Hurstville residents, Joseph Walker Bibby and Lochrin Tiddy to take up a petition to have Hurstville similarly incorporated. Tiddy was the retired headmaster of Hurstville School while Bibby was a well known Sydney company secretary and auditor and man of very substantial means. He had settled at the corner of Forest Road and Webber’s Road in the early 80’s on land formerly owned by George Perry. Here he built a fine home distinguished by its “fire-extinguisher” tower from which magnificent views of the surrounding country could be obtained. The grounds were beautifully laid out with ornamental shrubs whilst a wide lawn lay between the house and Forest Road. In later years one of Bibby’s daughters became Lady Riddell, wife of an early Governor of the Commonwealth Bank.

On March 28, 1887, the Hurstville Municipality was proclaimed and the first Municipal Election held at the Blue Post Inn on June 15, the same year. Lochrin Tiddy acted as returning officer. The results of this election are of interest —

Elected:

| Alexander Milsop | Capitalist | 244 |

| H. Patrick | Capitalist | 222 |

| W. J. Humphrey | Contractor | 217 |

| A. E. Gannon | Capitalist | 193 |

| J. Peake | Farmer | 189 |

| H. P. Tidswell | Merchant | 187 |

| J. W. Bibby | Accountant | 177 |

| M. McRae | Landed Proprietor | 167 |

| C. Howard | Capitalist | 165 |

The unsuccessful candidates were —

| D. J. McLean | Merchant Salesman | 162 |

| W.C. Corbett | Fruitgrower | 157 |

| H. Kinsela | Landowner | 129 |

| D.J. Treacy | Produce Merchant | 117 |

| H. Roberts | Builder | 91 |

| W.E. Paine | Carpenter | 73 |

| W. Harden | Stonemason | 62 |

| R. Wilson | Contractor | 57 |

Carlton’s representatives met with mixed success. Former Carlton resident, Alexander Milsop, who topped the poll, was elected Hurstville’s first mayor. Joseph Bibby, not surprisingly, was also elected to the Council but William Harden and Robert Wilson finished at the bottom of the poll.

Carlton subsequently became part of the Bexley Ward, by far the most closely settled of the three Wards which went to make up the new municipality, and it is reported that between 1887 and 1890 Bexley Ward increased in population by some 469 souls and numbered 363 houses, 13 shops and one hotel, the vast majority of which were clustered in small groups around the station at Carlton or along Webber’s Road.

Rumblings Of Discontent

As early as March, 1901, the residents of Carlton began to have grave misgivings about the advantages of their newly won Municipal status. The progress and reforms which they had been promised showed no signs of eventuating. The Council was experiencing severe financial difficulties; what few improvements were made, had been provided in Bexley and the kindly J. W. Larbalestier appeared to be a tool in the hands of the “Bexley Clique” as they sweltered over their problems in the oppressive summer of 1901. It was about this time that moves were made to build Bexley’s Town Hall at Carlton — a move which was probably influenced more by the presence of reasonable means of refreshment than by geographical convenience. The Council continued to meet, however, by the light of a kerosene lamp in the school room of the Rev. C.J. Forscutt’s Rockdale College in Gladstone Street, Bexley.

A protest meeting of ratepayers in Grant’s Hall presided over by Mr. W. Wiseman was assured that all was well but the great majority remained sceptical. The three worst problems were the water-course which ran under Short Street and Webber’s Road, known as the West Kogarah Drain, which was the favourite dumping ground for everything from discarded mattresses to discarded horses; the inadequate rail facilities both at the Station and on the trains and, of course, the straying stock which wreaked havoc on the gardens and nurseries which abounded in the area. One Council correspondent, Charles H. Everson, complained of being attacked by a stray cow in Mill Street. Another had run over a goat in Carlton Parade, “breaking his cart” and “receiving an injury” to himself.

At last it was decided to prevail upon the redoubtable J. G. Griffin to take up the cudgels on Carlton’s behalf.

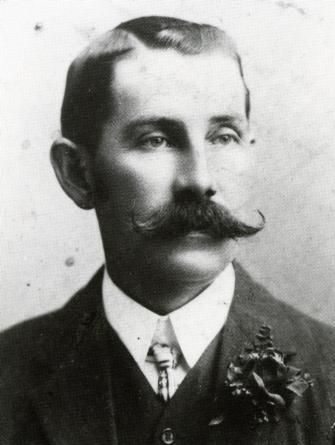

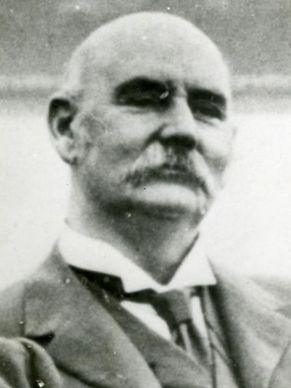

John George Griffin

Of all the people who have lived in Carlton since the opening of the railway, none was as outstanding a personality as Griffin.

John George Griffin was born in Richmond, Victoria, in 1846. He was educated in England and at an early age entered the service of the Great Western Railway Company where he qualified as a civil engineer and surveyor. He was engaged for two years on railway construction work in Bulgaria and Romania. Returning to Australia in 1867, he settled in Portland, Victoria, for a time as shire engineer. Later he came to Sydney where he set up in business as a surveyor being the principal of the firm of J. G. Griffin and Harrison, Surveyors. At one time he served as supervising engineer on the extension of the Great Northern Railway in N.S.W. He settled in Carlton in 1890 and in 1893 was elected to the Hurstville Council where his abrupt manner and an inability to suffer fools brought him into immediate conflict with his colleagues. For three stormy years, 1893, 1894 and again in 1898, he was Mayor of that Municipality. In 1896 he was the centre of a minor controversy. Having secured an overhead footbridge for the Station at Carlton, he refused to use it, continuing to walk across the railway lines in defiance of a notice he himself had erected forbidding it.

At the memorable Municipal Election of 1899 Griffin was strongly challenged in the Bexley Ward by Mr. W.H. Wicks, of “Dundry”, Ocean (now Verdun) Street. Wicks had the backing of such influential figures as Frederick Grant and John Cooper and wont to considerable pains to point out that Mayor Griffin had spent the entire coming year’s income of the Council without authority. Griffin, however, mobilised the resources of the Council to his side, using Council-paid employees as his scrutineers inside the booths and as his agents outside as well as employing them to drive known Griffin supporters to the polls in Council owned conveyances. Whilst the ethics of his actions could possibly be challenged, the success could not. From the time of his arrival in Sydney, Griffin had lived at “Thalinga”, No. 91 Mill Street, Carlton, yet he was for a period an alderman and Mayor of the Manly Council. He served five terms as an alderman of the Sydney City Council between 1900 and 1915 and for over 20 years he represented the Suburban Municipalities on the Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage. He was the first elected President of the Municipal Association which later became the Local Government Association and was a member from its inception. He was a strong supporter of the Free Trade Party and unsuccessfully sought election to the State Parliament for the seats of Hawkesbury and Marrickville. He once opposed Sir Henry Parkes for a city seat. He was an ardent advocate of a Greater Sydney scheme and was a pioneer of better working conditions for Council employees.

When the Borough of Bexley was formed he had been a candidate for the first Council, but had not been elected.

Such was the calibre of the man who was now called upon to plead Carlton’s case.

At the Municipal Election of 1902 Griffin topped the poll and almost immediately, the fireworks began. Griffin was a caustic critic whose utterances often stirred up angry feelings. He so harried the Bexley selected Mayor, Henry Watson Harradence, over the state of the West Kogarah Drain, the dangerous pedestrian crossing across the railway line from Gray Street Kogarah to Guinea Street and the unsatisfactory local safeguards against the outbreak of bubonic plague then assailing waterfront areas of the city, that Harradence attempted to silence Griffin by pointed and repeated references to “The Chain Letter Scandal”.

The Chain Letter Scandal

At a packed public meeting, held on May 30, 1902, at the Royal Hotel, Griffin made the following explanation.

In 1895, whilst a member of the Board of the St. George Cottage Hospital, he had read in the London Times a letter advocating the use of chain letters for charitable appeals – each letter to contain ten postage stamps which would subsequently be sold. He had suggested to his 17 year old daughter, Audrey, that this would be an excellent way to raise money for a much needed children’s ward at the hospital.

It was hoped to raise £25 in this way which, with the government subsidy of £1 for £1, would contribute £50 towards the appeal. The scheme was not only a spectacular success but soon got completely out of hand. Hundreds of letters arrived daily at the Griffin home in Mill Street from places as far away as England, America and the Continent. After £64 had been contributed to the hospital Griffin decided his daughter could no longer cope and he put on a man to handle the matter at his office in the Equitable Building in the City. When the £64 was handed to the hospital committee they refused to devote it towards the erection of a children’s ward.

Griffin thereupon refused to hand over any more money and protracted legal manoeuvres ensued. Finally, Griffin resigned from the hospital board and wiped his hands of the whole matter.

Ugly rumours persisted that Griffin had used the money for his own purposes and a Royal Commission was demanded. Griffin denied making money from the venture, producing evidence to show that all money received after the initial payment of £64, had been taken up in wages and legal fees.

Griffin was accorded an overwhelming vote of confidence whilst Harradence was greeted with cries of derision. One persistently noisy interjector was flattened by the editor of the “St. George’s Advocate” who was having difficulty in hearing Griffin’s explanation.

Round Two

Having failed to discredit Griffin in this manner, Harradence adopted a ruse that was as clumsy as it was petty.

After the minutes of the Council Meeting of September 29, 1902, had been confirmed, Harradence privately instructed the Council Clerk, Hector Wearne, to insert a motion in Griffin’s name to the effect that all persons owing £2 or more in rates were to be prosecuted. Times were still hard – particularly in Carlton and the Council received many requests during these years from insolvent ratepayers to work out their rates.

Griffin indignantly denied having moved such a motion – pointing out that he had not even been at the meeting on the night he was supposed to have moved it. Harradence, realising his folly, then tried to erase the motion with acid but succeeded only in making several large holes in the pages of the Minute Book.

There then followed three stormy meetings.

At the first, Griffin, backed by a cheering gallery of Carlton residents, demanded the resignation of Harradence as Mayor. This motion was carried with Harradence as the sole dissentient – even his Bexley colleagues could not countenance this action.

Then Griffin demanded an explanation from the Council Clerk. Much against Griffin’s wish it was decided to hear this explanation in closed Council. The packed gallery was understandably upset. Griffin was beside himself with rage. He swooped down on the one and only copy of the Council by-laws, rolled them into a ball and threw them at J. W. Larbalestier, who had replaced Harradence as Mayor.

He refused to resume his seat but threw open the windows and relayed proceedings to the excited crowd outside.

Mr. Wearne tendered his resignation as Council Clerk.

Finally, Griffin moved that Harradence be proceeded against for “altering, mutilating and defacing the minute book of the Bexley Council” but was ruled out of order for his “boorish, ungentlemanly and offensive conduct”.

This article was first published in the August 1964 edition of our magazine.

Browse the magazine archive.