by Ron Rathbone

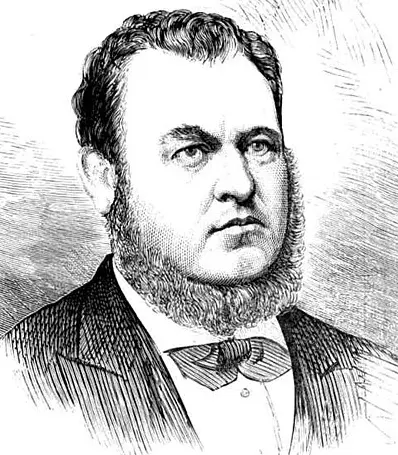

Of all the members who represented the Canterbury Electorate or its predecessors, which covered the St. George District until 1893, none proved as energetic, capable, effective or painstaking as John Lucas. Broad shouldered and inclined to be both assertive and bombastic, he had a great fighting heart and a vision and an intellect which made him one of the outstanding figures of the Legislative Assembly. Born in Newtown in 1818, he was the grandson of an officer of the NSW Corps. At 16 he was apprenticed as a carpenter and subsequently became a builder and contractor. For many years he lived in Bridge Road, Camperdown.

From his election in 1860 he waged an unrelenting war against the government, whatever its composition or political complexion. His abhorrence of waste made him many enemies by constantly seeking economies in the public service and curtailment of its perquisites. He had a morbid interest in the acquisition of land for cemeteries and a detestation of dancing and music in public houses but perhaps his strangest request occurred on 5 March 1861, when he formally and understandably unsuccessfully moved that the plush green leather seating in the Legislative Assembly be changed from stuffed cushions to cane.

It was to his credit that for the next twenty years as an unapologetic protectionist, he held one of the safest Free Trade seats in the colony.

Perhaps his success was due to the fact that he never lost touch with his electors, shrewdly avoided committing himself on unpopular issues and during his first term secured huge concessions from the government to repair the Cooks River Dam and bridges in the southern part of his electorate.

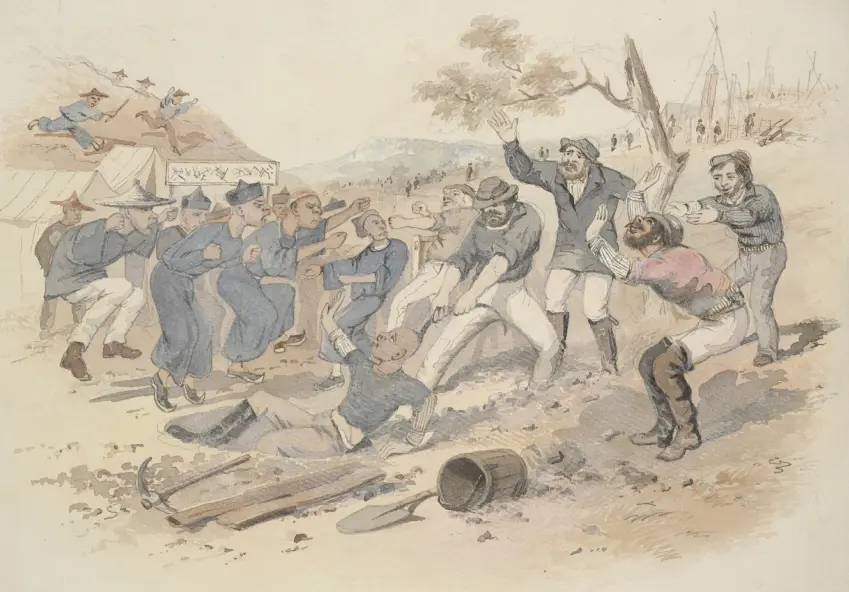

It is not generally known that it was largely due to Lucas’s efforts that the Jenolan Caves were opened up and proclaimed as a public reserve – one of the caves today bearing his name, but it was his one-man crusade during 1860 and 1861 to have restrictions placed on the entry of Chinese immigrants to Australia which first brought him into prominence.

Lucas was one of the first members of Parliament to realise the danger of unrestricted Oriental immigration and against bitter opposition, he persisted in his efforts to have a poll tax placed on each new arrival. After the serious Lambing Flat Riots of 1861 in which one white man got himself shot in the knee and a number of Orientals lost their pig tails and very nearly their lives on the goldfields around Young, the Government adopted his proposals – the forerunner and foundation of today’s White Australia Policy.

In May 1860, Lucas caused a sensation by demanding the removal of Judge Cary from the District Court Bench when the learned the judge told his jury he felt like sending them to do hard labour on Cockatoo Island Penal Settlement as well as the prisoner they had just convicted, remarks, Lucas claimed to have been occasioned entirely because Cary’s son had been the prisoner’s defence attorney.

At the election of 1865, Lucas was opposed by Alderman James Oatley, the popular Goulburn Street Publican who was Mayor of Sydney in 1862, and whose father had been keeper of the Town Clock. He was also opposed by two quite delightful characters named John Beer who, despite his name, was a most ardent and uncompromising temperance advocate and Tertius Thomas Rider, whose vocabulary rivalled that of a bullock driver and who delighted the electors of Canterbury by proclaiming from the hustings that he stood for “free land, free trade, free education, in fact every bloody thing that was free.”

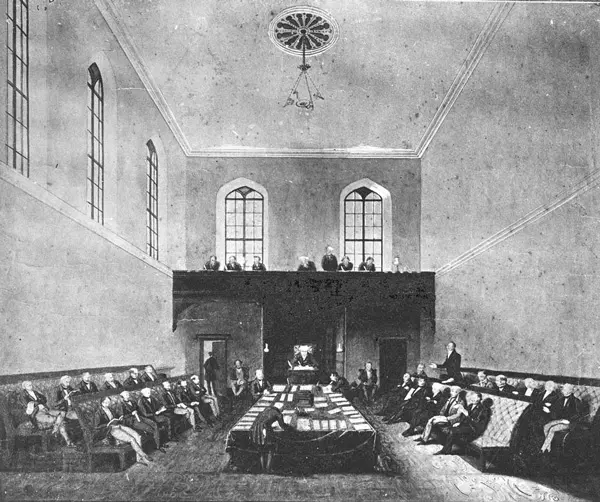

This same year Lucas gave evidence before the select committee which investigated the problem of Sydney’s ever dwindling water supplies. The Botany or Lachlan Swamps which had supplied Sydney for many years were becoming inadequate, polluted and filled with drifting sand.

Former Canterbury member, Edward Flood argued strongly in favour of using the waters of Cooks River and its tributary Shea’s Creek which drained the heavily populated and largely unsewered suburbs of Redfern, Alexandria, and Waterloo with their many slaughterhouses, knackeries, and boiling down works but was heavily polluted even at that stage. John B. Carroll of Kogarah and Hon. Thomas Holt propounded the quite fantastic scheme of damming the Georges River at Rocky Point, Tom Ugly’s Point or Kangaroo Point. This was also ruled out by the commissioners because of the unreliability of its tributaries and the high mineral content of the Georges River basin – though it was admitted that in spite of certain additives from the paper works and wool wash, the inhabitants of Liverpool appeared to thrive on the aqua pura from this river.

Lucas poured scorn on both schemes and proposed a system of dams on the Woronora, Upper Nepean, and Warragamba Rivers. 50 years later this scheme was adopted in its entirety and almost 90 years later the mighty Warragamba Dam was completed.

In 1868, Lucas encountered his first serious opposition in the Canterbury Electorate when William Henson, lawyer, temperance advocate, and Methodist lay preacher, nominated against him.

Henson was enthusiastically embraced in the St George section of the electorate which at this time had the highest proportion of Methodists of any part of the colony. Such prominent local families as the Peakes, the Bowmers, and Beehags flocked to his cause. Henson was a particularly vitriolic individual and taunted the retiring member with being a hypocrite and insincere. He accused Lucas with having the toll bar moved to the far side of a property he owned at Punchbowl so he didn’t have to contribute towards the toll and of keeping £120 worth of toll money from the Punchbowl Salt Pan Creek Road which as a trustee he was responsible for spending. Henson went on to accuse Lucas of having his sons promoted in the public service at a time when its staff were being retrenched, and of having their salaries increased whilst others were having theirs reduced as a part of the government’s economy measures. In the closing stages of the campaign Lucas’s horse bolted and his sociable overturned rendering him insensible and a large sympathy vote ensured his return.

In 1873, Lucas was appointed Secretary for Mines and it was largely due to his persistent representations that the government ultimately agreed to the construction of the long-projected Illawarra Railway Line. This measure was enthusiastically received by the people of St George who on June 8, 1876, drew up a petition “noting with extreme satisfaction the fact that the government had placed on the loan estimates for the year a sum of money for constructing a railway from the deep waters of Sydney Harbour to Wollongong to bring to the doors of the city an unlimited supply of cheap coal and an abundance of fresh pure cheap milk and other products from the want of which much illness and unnecessary suffering is inflicted on the rising generation of the city”.

The whole question of the Illawarra Railway was bitterly opposed in another very largely signed petition from the inhabitants of Newcastle.

In June 1875, Lucas officially opened the first government school at Hurstville which at that time was the show place of the state. It was described as “an excellent building of hewn freestone lacking only a bell, two chairs, a lavatory for the boys, and the inscription ‘Public School'”.

But perhaps the outstanding event of Lucas’s term as Secretary for Mines was his securing of an area of crown land in every town in NSW for dedication as a public park.

At last, in 1880, Lucas decided to call it a day but was immediately appointed to the Legislative Council where he remained a much valued member until his death at the age of 84 in 1902.

The following election saw the persistent William Henson elected to the Legislative Assembly although he refused to address his electors outside a public house because of the unrighteous traffic in alcoholic liquors.

And for the next three years the Legislative Assembly was in constant uproar.

In October 1881, during the bitter anti-Chinese debates he seriously questioned whether Chinese tea was fit for human consumption and in January 1882 vehemently opposed the purchase of a billiard table for members of parliament on the grounds “that the expenditure of public money on such an implement of pleasure, delight, and diversion was unwarranted and unjustifiable and calculated to absorb in idle amusement many hours of members’ time which should more patriotically be devoted to affairs of state”.

Two months later he failed to get a seconder when he moved to have the parliamentary refreshment rooms de-licenced and was equally unsuccessful in attempts to have boxing banned, private bars in hotels abolished, and to prevent the use of public houses as polling booths.

During 1883 he conducted the Royal Commission on Noxious and Offensive Trades on an extensive visit to his electorate. In their report Mr. Barden’s boiling-down works and slaughter house at Kogarah were described as passably clean; D. Chapplow’s poultry farm was not very so, whilst Henry Latham’s piggery adjacent to the Illawarra Railway Works near the Cooks River Dam was described as being in a filthy state. The Commissioners encountered more pigeons than they had seen anywhere else in the colony at Solomon Dominey’s Pig Farm near Gannon’s Forest but it was at Godfrey and Moon’s Boiling Down Works and slaughter house between Rocky Point Road and Seven Mile Beach that their journey to the district really became worthwhile.

This dreadful establishment which processed the offal from some 50 of Sydney’s butcher’s shops produced 5 tons of tallow and 1000 tons of bone dust a week. It also boiled down on instructions from the police most of Sydney’s unwanted dogs, goats, and other discarded domestic animals, their skins going to the nearby tanneries at Botany whilst their fat was used to dress leather and to make candles. The stench from this enterprise was described as “abominable and foul beyond description”.

Henson was still member for Canterbury when the Illawarra Railway Line was opened as far as Hurstville in 1884.

This article was first published in the May 1966 edition of our magazine.

Browse the magazine archive.