by Laurice Bondfield

Several years ago near Christmas, I went looking for a recipe for Christmas cake. The recipes I’d tried from modern cookbooks had not turned out to taste as good as I remembered from childhood, so I went searching for older cookbooks using imperial measurements in their recipes. Stuck in the back of a drawer, battered, torn, with pages coming loose and yellowing I found my mother’s electrical cookbook. Having found the fruitcake recipe in it no different to the ones I had not liked, I began to look through the pages, at first attracted by the old fashioned advertisements but then by the idea of the book itself, so I began to examine it more carefully.

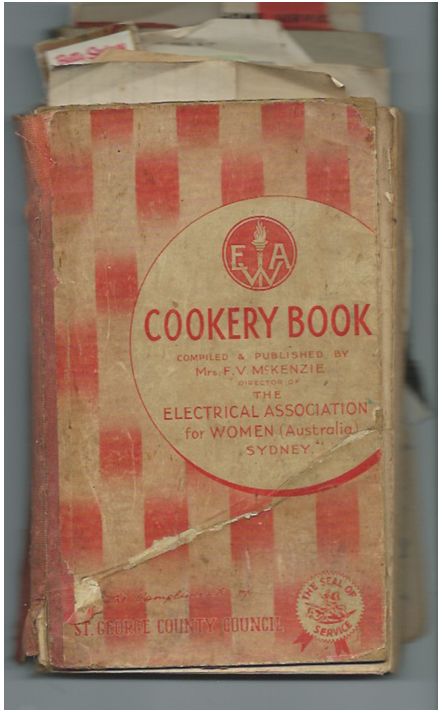

The cardboard cover was printed in a red and pink checked pattern featuring the title and “Issued with the compliments of St George County Council” with the familiar logo of St George slaying the dragon, and the inside front cover told me that it had been issued by “St George County Council Electricity Supply Undertaking”. A black and white photo showed twelve women in a cookery classroom, of which the text informed me that there were two – one at Kogarah, another at “Electricity House”, Hurstville. The text also let me know that free cookery classes ,”open to all St George residents” were held weekly and that they “also provide advisory services to women in their homes.” The opposite page showed that it had been “compiled by Mrs F.V. McKenzie, Director of the Electrical Association for Women (Australia), 9 Clarence St, Sydney” and that it was the third edition published in 1940. This gave me plenty of ideas to consider and mysteries to solve. Why did my mother need to take classes in electrical cookery? Who was Mrs. F.V. McKenzie and the Electrical Association for Women? How was this association connected to a cookbook issued by St George County Council?

The first question caused me to consider the way society copes with new technology. Today we press a switch and the light comes on, plug a kettle, a heater, an iron and any number of devices into a wall socket and think nothing of it. But I was reminded of a story by American humorist James Thurber about an eccentric aunt of his who was quite convinced that electricity was “leaking” into the air from the lights or wall sockets to the detriment of the health of the inhabitants of the room. We might laugh at her but we often think of dangers in the unfamiliar by analogy to something we do know, in her case obviously gas heating and lighting. Do you remember when microwave ovens first became common? Not only were new cookbooks written for novice users but there were all sorts of rumours about microwaves “leaking” out of badly sealed oven doors and causing harm to users among other dangers.

So not only would an authority (in this case, St. George County Council) want to accustom more people to using electricity, which they supplied, but to use it safely and to dispel any myths about its dangers. The book not only encouraged women to use electric stoves but published advertisements giving ideas about other appliances using electricity for lighting, heating, cleaning and washing in the home which could change the lives of housewives and, of course, to increase the use of electricity that St. George County Council provided (courtesy of the Commissioner for Railways from 1923 – 1952) (1). After all, women in the 1930s were still using cement washing tubs, gas or wood burning coppers, clotheslines,clothes props and externally heated irons just to do the washing and ironing, let alone the other tasks which fell to their lot. As the notice on page 39 about other services available from the County Council points out, “This is an electrical age, and most of the daily tasks of humanity can be done better by electricity than by any other method.” St. George County Council gained a reputation in the 1920s and 30s for the innovative ways it used to promote the use of electricity. For example, women demonstrators were sent from the Council to any furniture store which was having a promotion of electrical equipment, especially stoves. A photo from the book “St George County Council Electricity Supply Undertaking First Fifty Years 1920-1970” shows an early electric cooking demonstration at Diment’s Store Hurstville. Another shows a “demonstration platform” which could obviously be moved from place to place as needed for cookery demonstrations. The slogan above the platform reads “Cook by electricity. Cool and Convenient. No Waste. No Fumes”. Later, demonstration kitchens were opened in Kogarah and Hurstville headquarters as mentioned before. Other clues to making the housewife the “electrical expert” in the home come on page 31 “A Page for Menfolk” headed “Tell your menfolk about these risks!” on how to avoid accidents involving electricity. The page has three photos: one of a man on a ladder painting the guttering perilously close to the wires supplying electricity to the house, the second showing a man in a shed using a lathe plugged into a possibly faulty light fitting, and the third has a man using a portable electric lamp to check under the house footings, warning that a faulty lamp socket or cord could cause the current to earth. Each photo has a dotted line showing the earthing effect of an electric current through the body in each case. Page 38 headed “Safety First” advises that all appliances and flexible cords should be kept in perfect order accompanied by two photos. One of a boy (“Neville Musto kindly posed for this picture”) about to touch the electric wires exposed by a frayed cord on an iron, another of a boy about to climb up to a shed roof to retrieve a kite hanging dangerously from the electric wires. There are other pages devoted to explaining safety in the kitchen – including an electric hairdryer! – and the safe use of an upright vacuum cleaner.

Last of all, with an eye to future users and their preservation is a children’s page which explains about the “tiny electric imps sent out from the power station, along the copper wires you can see high up on poles in the street”, how to avoid the electrocution of your pet cat, why birds are safe sitting on wires, and why you must never go near fallen power lines. This was published in the “School Magazine” (which many of you may remember getting free each month in primary school) several times over the years. It was written by F.V. McKenzie, who invited her readers to write to her “if you want to know more about the Electric Imps” which brings me to my next question: who was Mrs F.V. McKenzie?

The search for an answer to this question at the beginning of my research sent me to the Dictionary of National Biography – nothing. My question went unanswered for a few years until an article in The Sydney Morning Herald in April 2012 put me on the track. This year serendipity came to my aid! After showing the cookbook at a “Show and Tell” session of the Society the RAHS e-newsletter appeared in my inbox. In it was an advertisement for a talk at Benledi House, Glebe on “The Electric Violet McKenzie” by Catherin Freyne of the Dictionary of Sydney!(2) This filled in a lot of the gaps in knowledge. Catherine Freyne and Lisa Murray have researched Violet McKenzie’s life and Catherine Freyne has published a detailed biography on the Dictionary of Sydney website, along with an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography. Research into her life is ongoing.

Violet McKenzie (nee Wallace) was born in 1890 in Melbourne. Her family moved to Austinmer on N.S.W south coast when she was small. By her own account she was always interested in bells, buzzers and lights as a child and successfully set up an automatic light in one of the dark household cupboards. After completing primary school she won a bursary to study at Sydney Girls High School. In 1915 she studied science at Sydney University, then approached Sydney Technical College to study electrical engineering.In an oral history recorded in 1979 she recounted her reception! She was told students were apprenticed to a firm, so showing the enterprising spirit she maintained through her life, she had some cards printed with her name as an electrical engineer, found an advertisement in a newspaper requiring someone to install electricity to a house “way beyond Marrickville, a mile from the end of the tramline.” Could it have been in our district? She presented her business card and the contract at the College and was accepted as a student. She graduated in 1923.

For many years she ran a successful radio shop in the Royal Arcade in Sydney, becoming the only woman member of the Wireless Institute of Australia. Early radios were not easy to use, and enthusiasts like Violet were often radio hams as well, learning Morse Code to send signals. By 1932 she had set up the “Women’s Radio College” on Phillip St, Sydney where she provided training in Morse Code and how to build and set up radio receivers. In 1924, she had married Cecil McKenzie, a young electrical engineer employed by Sydney County Council. It was this connection which, in my opinion, later led to Violet creating the “Electrical Association of Women”. To see why she did, we have to look at the different ways that St. George and Sydney County Councils were set up to supply electricity to their customers.

The St George County Council, the first of its kind, was set up in 1920 when Bexley, Hurstville, Kogarah, and Rockdale Councils were faced with increased charges for the supply of gas, particularly for street lighting, just at the time the Illawarra Railway was being electrified. The St. George District was becoming increasingly suburban. Small farms were being sold to developers for new estates, houses were being built near the railway stations for the new “commuter class” like my grandfather, Ernest Bondfield, who lived in Grey St, Allawah with his young family and took the train to the city to his job at the Lands Title Office, even before electrification. Thus St George County Council was in the enviable position of having very little existing gas supply infrastructure, lots of customers keen to live in “modern” homes and a readily available source of electric power, that could be sold at low cost. The original St. George scheme had been to erect distributors to supply 2,000 consumers in 5 years but within 12 months mains had been erected to serve over 10,000. In contrast, Sydney County Council faced a city which had built gas pipes and generators in the early twentieth century to supply heating and lighting to both residential and commercial premises. Moreover SCC had to build their own electric power stations, like White Bay, which increased the initial cost of setting up a reliable supply. Potential customers in Sydney already had gas heating, lighting, and stoves which worked perfectly well – why would they change? The best way to increase residential electricity demand was to increase the use of electricity for heating, lighting, and cooking. Both Councils had had to obtain loans to begin initial construction of a network and they were keen to repay them. In 1922, the City Electrical Engineer, H.R. Forbes complained of “thousands” of consumers whose annual consumption amounted to 70 – 140 KwH whose only use of electricity might be for a radio or gramophone, perhaps a reading lamp(3). So any way that householders could be persuaded to use more electrical appliances was to be encouraged.

In 1934, Violet McKenzie, set up the Electrical Association of Women in King St, Sydney. Photos from the time show a room that was part electrical demonstration showroom set up by Sydney County Council part club room. Violet McKenzie was keen to educate women about the generation and use of electricity – the club room had a poster diagram of an electricity generating power station as its only art work! Any woman who was interested in buying anything from an electric jug to a stove could come in and learn how to use it free of charge. In 1936 she published the EAW Cookery Book, which ran into seven editions and remained in print till 1954. Obviously at some stage St. George County Council had obtained permission to publish an edition for use in its cookery schools with its own cover, the 1940 edition of which was my mother’s cookbook. You can see how the innovations pioneered in St George were adapted to suit Sydney County Council’s different circumstances.

Violet McKenzie went on to have a distinguished career. In 1939, she founded W.E.S.C. (Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps) to train women in Morse Code to replace the male telegraphists in the Post Office who would be called up for military service when war broke out. By the time war was declared she had trained 120 women. She was instrumental in persuading the RAN brass to set up the WRANS by proving to them that women could use radios just as well as men. Throughout the war she trained men and women in the Army, RAAF, and merchant navy operators including contingents from other allies such as India and USA. No government grant or allocation of accommodation was ever given to her, the WESC instructors paying 1/- per week towards the rent of the premises housing the school. By war’s end she had trained over 3,000 women, one third of whom joined the services, others remained at Clarence St as instructors. The only official recognition she ever received during wartime was to be made an honorary Flight Officer in the WAAF so she could legitimately train Air Force personnel. After the war she continued to train men for the merchant navy, commercial pilots and anyone who needed a “signallers’ ticket”. Many of them spoke affectionately of learning with “Mrs. Mac.” In 1950 she was awarded an OBE for her wartime service. She died in 1982.

This brings me to the final question – Why did my mother need to learn to cook on an electric stove? Well, in 1939, she and my grandparents moved to a rented property in Arncliffe. I suspect the house had an electric stove, which she hadn’t used before, and probably attended cooking classes at one of the St. George County Council kitchens, purchasing or being given the 1940 edition of book after finishing the course.

So, so far I have found answers to some of my questions, only to raise others. Who were the “lady demonstrators” employed by the St George County Council, especially the “Home Service Supervisor, Mrs Gardiner”? There also seem to have been quite a number of women clerks/ typists employed in the Council offices – remarked on in passing in one of the two histories of the Council but their experiences never detailed. If anyone knows of any information about them, especially in the period 1920 – 1940,I would love to find out more!

Finally, a foreword in the EAW Cookbook by Dr. Frances McKay, led me to search in a different direction again – but that is the subject of another article.

Notes and References

- St George County Council Electricity Supply Undertaking: The First 50 Years 1920-1970.

- Dictionary of Sydney. https://dictionaryofsydney.org/person/mckenzie_violet

- Electrifying Sydney: 100 Years of Energy Australia by George Wilkenfield and Peter Spearitt. Sydney 2004.

- St George County Council: 12 Years of Progress 1920- 1932.

This article was first published in the January 2016 edition of our magazine.

Browse the magazine archive.

A fascinating article and Violet McKenzie was a remarkable woman.

When I first married in 1977, microwaves were still very new. We purchased a microwave and with it came complimentary lessons on its use. So I can identify with the need for training people in the use of electrical products.

Thank you for this fascinating article.